Checking type annotations at runtime—in addition to statically—is a net win in a gradual type system. In many cases runtime checking only seems like it comes with more costs, when in fact they’re the same costs, paid earlier. When there are net-new costs, there are ways to minimize them, and runtime-checked type annotations come with some key benefits that makes working in a gradually-typed codebase easier.

Quick background

I’ve written this post mostly agnostic of language, but obviously most of my experience comes from working on Sorbet for Ruby. For context, adding a type annotation to a method in Sorbet not only instructs the type system to assume the method has that type, but also wraps the method at runtime in a shim method that asserts arguments and return values have the stated values on each call:

# Given a `sig` like this:

sig {params(x: Integer).returns(String)}

def integer_to_string(x)

x.to_s

end

# At runtime, `sig` acts like a decorator,

# making the method behave like this:

def integer_to_string(x)

raise TypeError.new("Wrong type") unless x.is_a?(Integer)

result = x.to_s

raise TypeError.new("Wrong type") unless result.is_a?(String)

result

endIf this is new to you, feel free to read any of these Sorbet docs:

With that out of the way, here’s how I respond to the most common complaints I hear about this choice.

Complaints about checking types at runtime

…and why I think they miss the mark.

“It’s riskier, because a types-only change might break the code”

Absent runtime-checked types, the code would have worked—why should adding a type annotation make the code break?

Remember: in a gradual type

system, the existence of types like T.untyped mean

that the static types can lie at any point in the program.

My claim: it’s just as risky to program against types that are subtly

wrong.

Runtime-checked type annotations incur the risk early and sharply, sure.

But when the types are subtly wrong, every change is risky, even small

ones like adding this if condition and print statement:

sig {params(params: Params, merchant: Merchant).void}

def handle_request(params, merchant)

if params.something_unlikely?

puts("Processing unlikely request for merchant=#{merchant.id}")

end

handle_request_impl(params, merchant)

endIt’s all too easy for some handle_request call site to

accidentally pass nil for merchant by way of

some untyped piece of code. Absent runtime type checking, adding this

if statement might not immediately cause a problem! But the

bug will be there, and the first time something_unlikely?

happens the code will crash on the call to merchant.id.

Runtime type checking makes broken assumptions fail early and loudly—this is not the same thing as more risky. In fact, most systems are better at absorbing early, loud breakages! Automated alerting quickly climbs above some threshold, stack traces immediately point to which assumption was violated, and rolling back is easy because hundreds of changes haven’t arrived in the mean time.

“It’s more work”

In addition to fixing the static type errors, I have to fix the test failures and roll out the change.

I think this is fair: it can be tricky to get tests to pass, especially if the code is making heavy use of mocks. But again I’ll say: I think the effort mostly the same, just front-loaded.

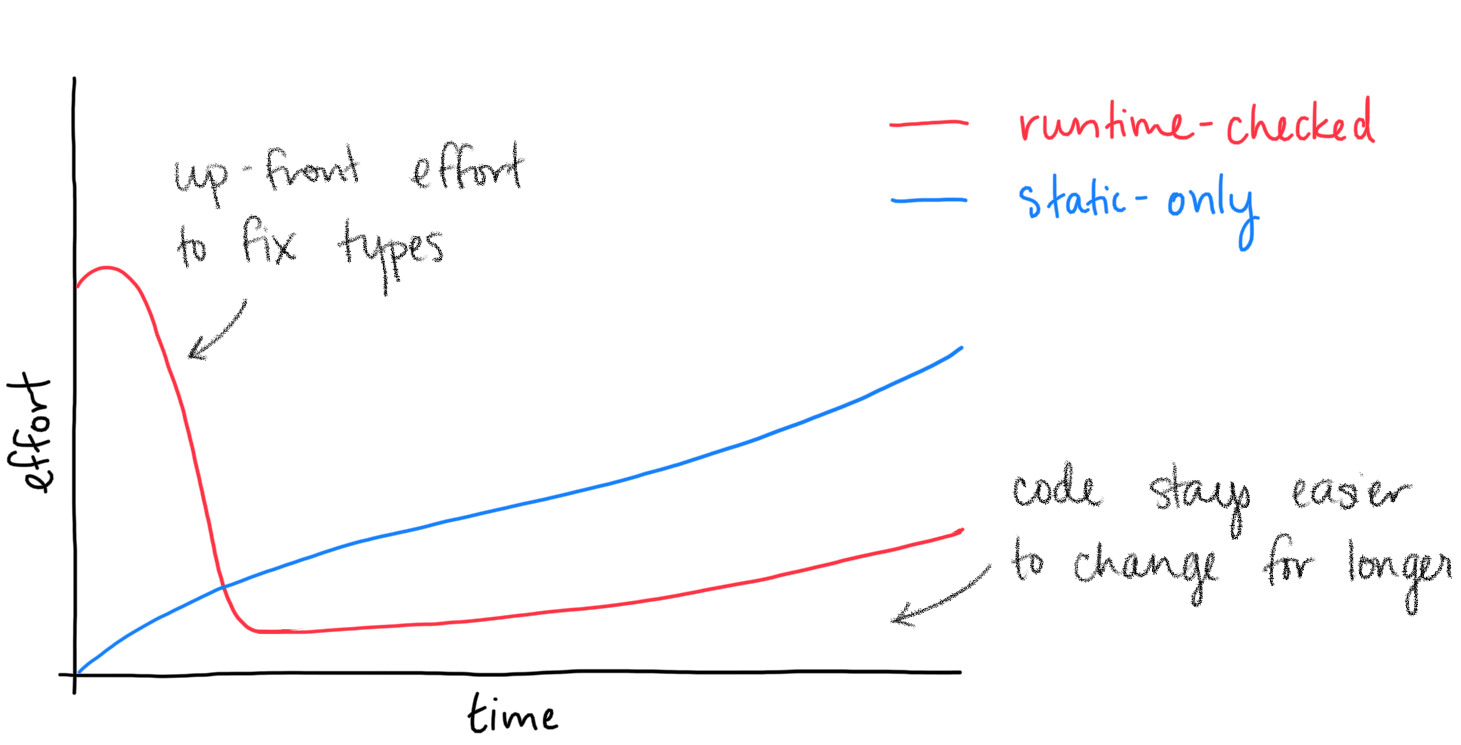

In my experience, overuse of mocks make tests brittle and tends to cause problems when refactoring code, regardless of whether types are checked at runtime. Checking types at runtime is a bit of a forcing function to move away from mocks and other hard-to-type constructs, which is a force multiplier on future productivity. In my head it looks something like this:

It’s not always a lot—sometimes it’s only marginally more work, and sometimes the runtime checks pay for themselves in the change they’re added if they happen to help as a debugging aide to get the tests passing.

Getting the runtime type checks to pass for the first time adds a lot of extra effort, but that extra effort makes the next change and the change after that a lot easier. Even well into the future, legacy code with runtime-checked types remains easier and less scary to change. Locking in the runtime-checked annotations early means that when going back to change 3-year-old code, these types are almost guaranteed to be trustworthy, making for far less work hunting down the truly correct types when modifying legacy code.

“Runtime checks slow the code down”

I can’t spare any performance to pay for the cost of runtime checking.

Slowing down the code is an unavoidable cost of runtime-checked annotations, no matter how you do the accounting. In cases where every millisecond matters, sure, you probably don’t want runtime checking. But I want to qualify this with a couple of points.

Not every use case needs to shave off every millisecond. Some applications can absorb a small slowdown in exchange for the benefits that runtime-checked annotations bring.

It really is milliseconds. At work, we have runtime type checking turned on even for our most performance-sensitive request paths, and the slowdown from runtime type checking amounts to about 5%. To put that in perspective, that’s the difference between a request taking 1,000 ms vs 952 ms.

If it happens to be more than milliseconds for your workload, the overhead usually blames to a handful of hot methods. In Ruby, at least, there are powerful, low-overhead profilers which can to expose the slowest methods, at which point it’s easy to opt those hot methods out of runtime type checking. This strikes a nice balance between performance where it matters and correctness where performance matters less.

Runtime-checked annotations actually allow the Sorbet Compiler to speed up code.This point is Sorbet-specific, but it’s worth noting that all VMs for dynamically typed languages have to do runtime type checks constantly, so there’s no reason why it has to be.

I wrote about this effect before: Types Make Array Access FasterThe Sorbet Compiler is an ahead-of-time compiler, which makes it easy to leverage type annotations in the compiled code. None of the Ruby JIT compilers currently take advantage of type annotations, but also I don’t think that’s a hard constraint—just something no one has looked into yet.

So while runtime-checked annotations are a (minor) cost today, in the future they could actually be a benefit. Of course, this is no consolation for people who have to make their code as fast as possible right now, which is again why I think it’s one of the few fair complaints.

“Runtime checks are strange”

Why can’t Sorbet just be more like TypeScript?

I get this one a lot, probably because of how popular TypeScript and Flow are for JavaScript. But in fact TypeScript and Flow are in the minority: Hack, PHP, MyPy, Typed Racket, Typed Clojure, Raku, and of course Sorbet are all gradual type systems all have some form of runtime type checking available.

Even among TypeScript programmers, some are envious of runtime-backed types (example 1, example 2).

(I think there are other circumstances explaining why JavaScript type systems specifically chose to elide runtime checks, but that’s probably best left to another post.)

Over time, the initial strangeness simply wears off.

Unique benefits from runtime typing

In addition to the benefits mentioned above (like how changing legacy code is less risky and less work), runtime-checked type annotations come with some unique benefits.

It enables dead code checking

Sorbet flags dead code statically. For example:

sig {params(x: Integer).void}

def example(x)

if !x.is_a?(Integer)

puts(x)

# ^^^^^^^ error: This code is unreachable

end

endSorbet flags that the highlighted line is unreachable, but it’s only safe for Sorbet to report an error here (not just a warning) by depending on the runtime checks. Absent runtime checks, any untyped code could circumvent the type system and trip this line. Static-only type systems like TypeScript opt to not report dead code errors on similar snippets for this reason.

Runtime-checked type annotations enable promoting dead code problems from warnings to errors, which means that problems like these actually get caught and addressed.

The implementation matches the API

Refactoring in a large codebase is a constant struggle with Hyrum’s Law—someone, somewhere is depending on your implementation, not your API. Runtime checking ensures that the types are not only a part of the API but also the implementation, so there aren’t as many subtle gaps for people to depend on.

For example, runtime checking means that a method’s callers don’t

rely on the method silently accepting a wider type than declared (like

our handle_request example from earlier). It also means

that people building an abstraction can use sealed classes, final classes,

and final

methods to limit how their abstractions are used, ensuring that

people aren’t secretly violating those contracts at runtime.

Testimonials and wrapping up

Some of the most prolific Sorbet users I know share my views. To share some quotes:

In a codebase that is 100% typed, I don’t think runtime checks are necessary. But because we are not in that ideal world (and partial typing is a great selling point for Sorbet) I actually love the runtime checks.

As much as I like TypeScript, Sorbet has the better trade-offs to me: When I read Sorbet code, I know it says something about production behavior. With Typescript code, I know it says basically nothing.

I love runtime-checked types. When they fail, they almost always indicate a bug I’d like to know about. They add a layer of safety to my changes and enable me to improve the structure of the code rather than just type it, since the types lead to improvements to method boundaries, etc.

Overall, while runtime checking comes with costs, I think these costs are usually either overstated or misunderstood. The benefits that come with runtime checking are unique and powerful, and in almost every case make up for the costs. With time, the initial strangeness of runtime-checked type annotations turns into a powerful programming aide.

Appendix

One disclaimer: I think that the tradeoffs change slightly for applications versus libraries. I’ve written this post from the standpoint of applications, because it’s the one I’m the most familiar with. I would love to say more about libraries too, but I need more time to gather thoughts there. (As always, if you want to share your takes I’m happy to hear them.)